IPv4 Deep Dive

Published: 2024-01-31

English: wild orang utans, Gunung Leuser NP, Sumatra

Date: 13 September 2009

Source: Own work

Author: Nomo michael hoefner / http://www.zwo5.de

IPv4 Deep Dive - A slightly on the spectrum look at IPv4 addresing and classes

Its the new year, I’ve been busy not hax0ring, learning Jiu Jitsu, and focusing on networking. Ok, maybe still doing some h4x0r stuff, but at a leasurely pace. My focus lately has been on networking…

Lets get to it. Less talk, more rock…

Where to begin…

Binary.

Yah know, how things used to be before it was a social construct… 1s and zer03s, true or false, yes or no, on or off, outie or innie.

An Int type in programming is made up of 32 bits, thats 32 1s, 0s, or combination thereof. A single IPv4 address can fit inside an Int, because an IPv4 address is exactly 32 bits long. If you don’t know that a byte is 8 bits, cache that in memory. Fun fact, half a byte is called a nibble.

“There are 10 types of people in this world, those who understand binary, and those who don’t” - l33t H4x0r n0nymouse po3t skholar

So where were we… Oh, the IP address. Its made up of 4 bytes, the number in each byte is always in the range of 0 to 255 exclusively. Did I use exclusively correctly? I mean that 0 is the minimum value and 255 is the maximum, giving 256 different possible values.

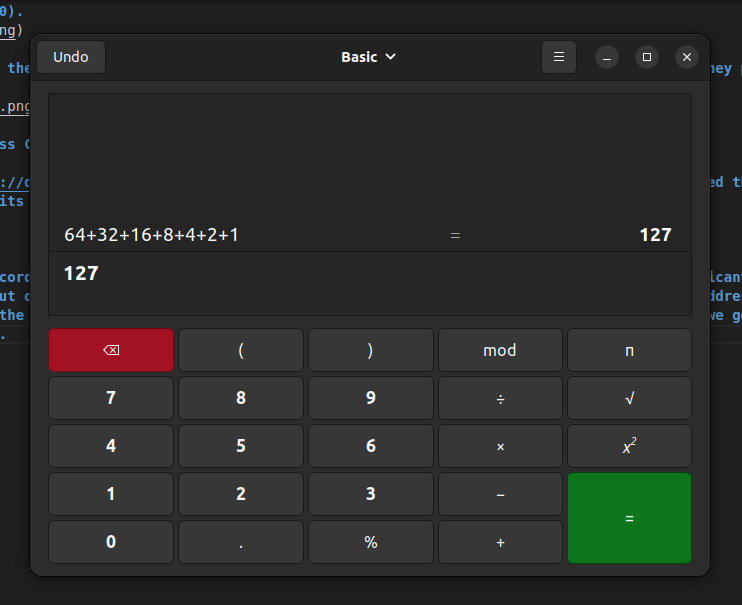

Why is the max value for a 8 bit binary byte 255? Because 1+2+4+8+16+32+64+128 = 255 Thats why. Ok, so a random bunch of numbers equals 255, what does that have to do with binary?

Binary has two options, 1 or 0, it’s called base 2. Hexadecimal has 16 options (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F) and is called base 16, decimal has 1-10 as options and is called base 10. Just remember base 2.

So, lets take the binary equavalent of the decimal number 10. 00001010 - Why 10? Because if you can remember 00001010 is 10, you know a binary number and are well on your way to great things. How does 00001010 equal 10 homie? Lets break it down…

Each byte (8 bits) has a low and high order bit. High order is on the left, low order is on the right (its just the way it is). Moving from right to left (low to high), we can convert the binary byte one bit at a time. I like to think of it as a game, each bit is worth a certain ammount of points, if the bit is a 1, you get points, if the bit is a 0, no points. So in a byte, we have 8 chances to score. Lets calculate the binary score of our decimal number 10.

Remember this???

“Why is the max value for a 8 bit binary byte 255? Because

1+2+4+8+16+32+64+128= 255 Thats why.” - Some Foo

Odd, 1+2+4+8+16+32+64+128 is 8 numbers, the same ammount of bits in a byte. These numbers are our scores, except they’re backwards. Lets flip them like a fascist coup de etat. Now we have 128+64+32+16+8+4+2+1, this is the correct scoring sequence for our binary number 00001010 (10 decimal, remember???). So starting from the right, we have a zero, then we have a 1 (score, worth 2), then a 0, then a one (score worth 8), followed by 4 0s. See how these Numbers map?

| 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 2 |

As you can see, after scoring we end up with an 8 and a 2. Thats a fun way to think about it, but there are also some mafs involved if you prefer…

| (times 2^7) | (times 2^6) | (times 2^5) | (times 2^4) | (times 2^3) | (times 2^2) | (times 2^1) | (times 2^0) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

10 = (0×2^7)+(0×2^6)+(0×2^5)+(0×2^4)+(1×2^3)+(0×2^2)+(1×2^1)+(0×2^0)

Fire up CyberChef https://gchq.github.io/CyberChef/ - Use the “From Binary” and “To Decimal” recipes. You’ll learn more by experimenting than I can teach. Type in

00001010in the input, it will be decimal 10 as output, alter a bit at a time to get instant feedback.

If you want a few more examples of converting binary to decimal maybe check this site out. https://www.rapidtables.com/convert/number/how-binary-to-decimal.html

Here’s a programatic version that converts a decimal number to an 8 bit binary byte, written in GoLang. It will take any decimal number, but starts over at 256…

go-convert-decimal-to-binary.go

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Print("Enter a decimal number to convert to binary: ")

var userInput int

fmt.Scan(&userInput)

binaryString := convertToBinary(userInput)

fmt.Printf("%d in 8 bits binary is %s\n", userInput, binaryString)

}

func convertToBinary(number int) string {

binaryRepresentation := make([]byte, 8)

for i := 7; i >= 0; i-- {

bit := (number >> uint(i)) & 1

binaryRepresentation[7-i] = byte('0' + bit)

}

return string(binaryRepresentation)

}Are we done with binary conversions yet? LET’s GO!

Where we going? Uhhh. Well, we need to break down an IPv4 IP address. An IP is made up of 4 bytes. An example is 9.9.9.9, which is dns.quad9.com. Each byte is a 9 (00001001). So the Quad9 IP is actually 00001001.00001001.00001001.00001001. What about 8.8.4.4, thats the Google alternate dns, the first 2 bytes are 8s (00001000), the second 2 bytes are 4s (00000100). 00001000.00001000.00000100.00000100. The point I’m trying to get across is that an IP can be segmented, we can slice and dice based on bytes and bits. We can say that 16 bits of the Google dns are 8s and 16 bits are 4s. Another DNS since we’re on the topic is 1.1.1.1 (Cloudlare - hey, have you guys unbanned my IP yet, jeez, it was only a Selenium bot. Oh, wait, I moved like 3 times since then. Nevermind…). You guessed it, 00000001.00000001.00000001.00000001.

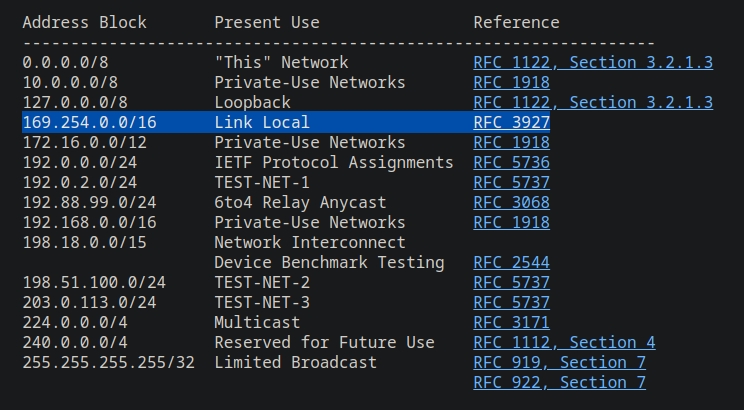

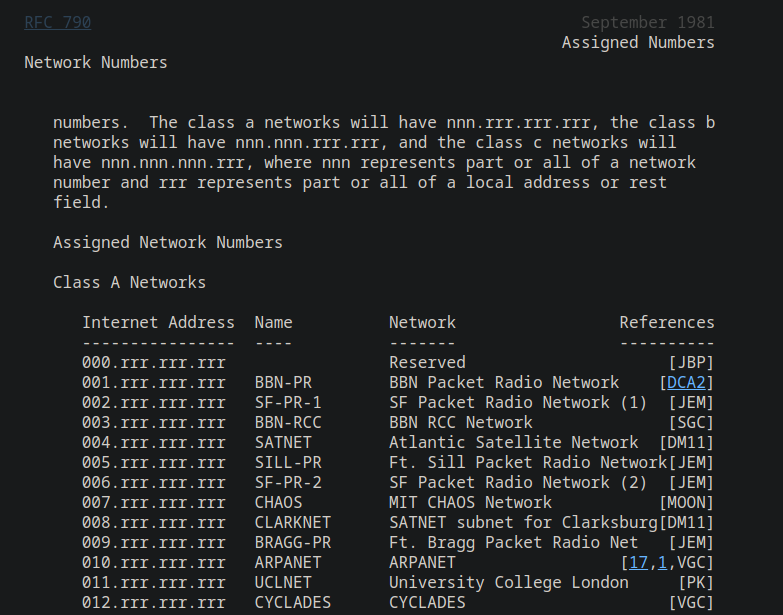

Its time we discussed classes. There are 4 classes I’ll cover, 5 total, but I legit don’t know much about the 5th one. So we have A,B,C, and D classes of IPv4 addresses. This is where all this binary stuff comes into play. Lets start with Class A. We’re going to reference some RFCs from 1981. The first RFC to check out is RFC 790 (https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc790).

A concept we need to have is network vs host address. We can have either lots of networks, or lots of hosts. Class A has the most hosts and the smallest network, with only 128 possible networks (0 and 1-127).

So, high level… Class A is only concerned with the first byte of the IP address, the network section, the last 3 bytes can do as they please…

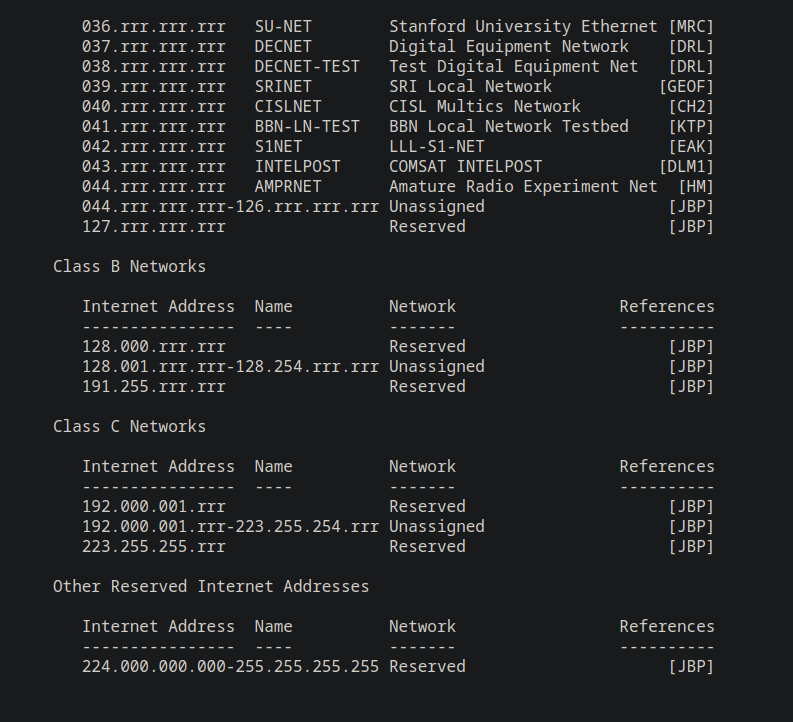

Class B is concerned with the first 2 bytes, Class C is concerned with the first 3 bytes…

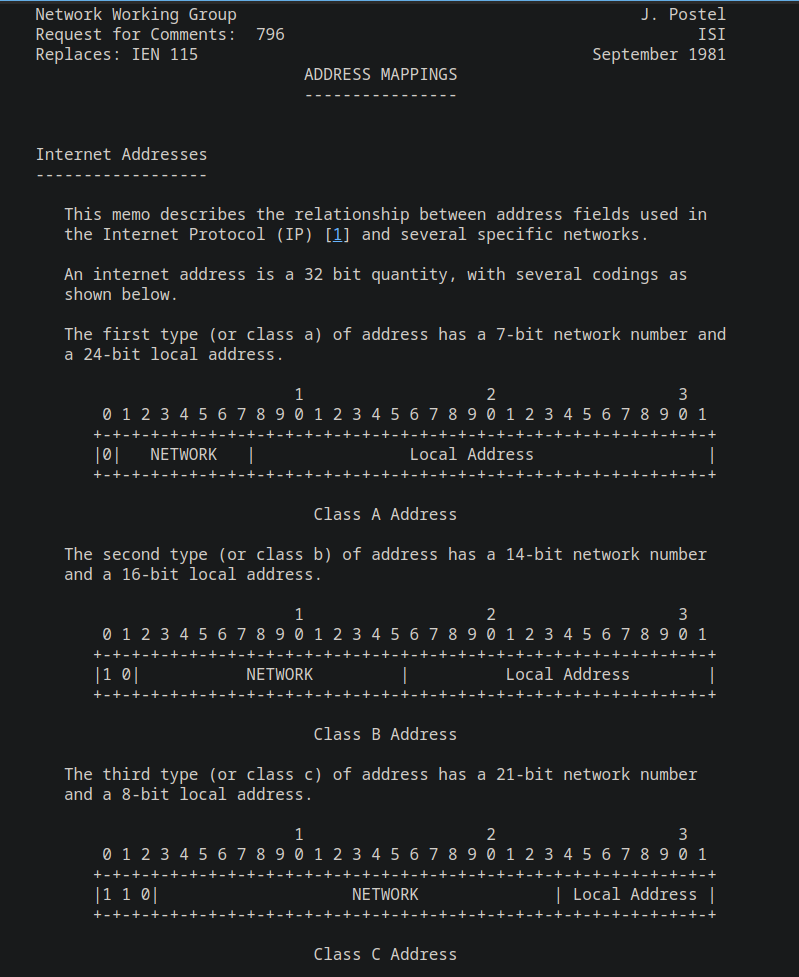

The second RFC we’ll check out is RFC 796 (https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc796). This RFC reiterates what we’ve covered thus far and introduces the concept of the highest significant bits being static depending on class.

Lets get back to the binary we know and love. According to this diagram, a Class A network must start with a 0 in the highest significant bit and the first byte is reserved for network assignment. So out of 8 network address bits, one bit is static (the highest, first bit) and 7 are variable. So, this tells us that 00000000 is the minimum address possible, and 01111111 is the maximum address available. Lets do the conversions. Copying and pasting from above, but excluding the highest order bit value (128, because it will be a 0) we get 0+64+32+16+8+4+2+1. Pasting that into my calculator that gives us…

Scrolling back up to RFC 970 screenshots confirms this. Class A is indeed 0 to 127 (128 addresses) or 00000000 to 011111111. We can also calculate the number of networks by using the formula 2^N where N is the number of bits used for the network address.

2^7 = 128 works for class A. The highest order bit is static, the remaining 7 (the N) of the byte are variable.

Lets take a look at Class B from RFC 796, we know that the highest order 2 bits need to start with 10 and we have a total of 16 bits available for network section. The minimum first byte value should be 10000000 and the maximum value should be 10111111. I can tell just by looking that the minimum first byte value is 128 (only a single 1 at highest order bit) and the maximum value of the first byte should be 255 (255 - 64), because the 64 score is the only 0 in 10111111. That gives us 191. Lets scroll up and see if I’m correct. So we have 128.0.x.x for the minimum value and 191.255.x.x for the maximum value in Class B. Lets do Class C… 110 is the static bit requirement, so 11000000 (128 + 64) is our minimum value and 11011111 (255 - 32) is the maximum value for the first byte. Minimum first byte value: 192, maximum first byte value: 223. Scrolling up to check our work…

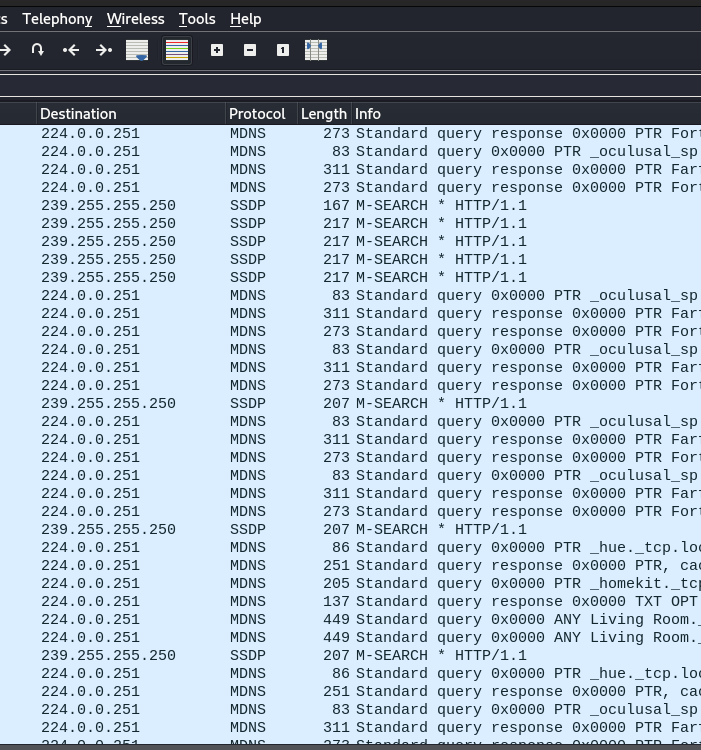

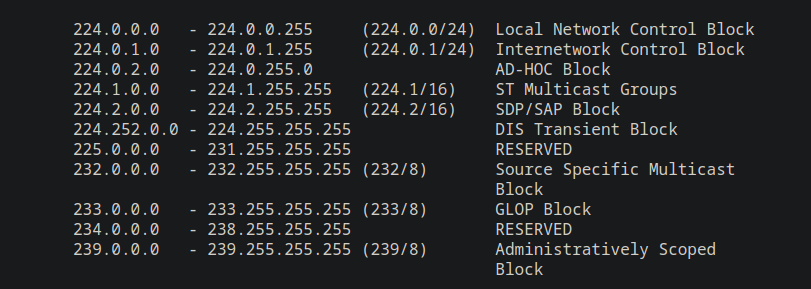

Class D. Deez Nutz. Ha. Got eem! Seriously tho, stop messing around, this is when we get into an important topic called Multicasting… Class D starts with the first 4 static bits 1110. The RFC for Multicast is RFC 3171 https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc3171 we can see that we have an expected range of 224.0.0.0 to 239.255.255.255, lets test this out… The minimum first byte value will be 11100000 (224) and the maximum first byte value will be 11101111 (239). Sweet! So our calculations make sense, what the hell is Multicast?

Multicast is kinda like a social media post… Your post is targetted at your connections or anyone following the post’s hash tags, your audience sees it in their feed, if they engage with the post (utilize a service or protocol) its up to them. One sees a lot of multicast traffic in Wireshark, understanding it helps us “filter” out the noise. See what I did there?

Broadcast is like a radio station or a web spider, it goes everywhere within range… Multicast is scoped. Multi - Many. Broad - Wide. More on broadcast later.

Just knowing that the multicast range falls between 224.0.0.0 and 239.255.255.255 can simplify your understanding of a pcap or Wireshark scan… Some of the interesting Multicast protocols are LLMNR, SSDP, NBNS, MDNS, and IGMP.

Wireshark filter for Multicast: ip.dst[0] & 0xf0 == 0xe0

ip.dst[0] extracts the first byte of the destination IP address.

& is the bitwise AND operator.

0xf0 is the hexadecimal representation of 11110000 in binary, which is used to mask the upper 4 bits.

== 0xe0 checks if the first 4 bits are equal to 1110 in binary.

RFC 3171 has a rad table for explaining CIDR, so I’m going to go off on a CIDR tangent for a minute. WTF is /24 or /8 or 255.255.0.0 or Netmask? Lets take a look a this table…

So, the /X number just means number of bits allocated to the network portion of the IP.

Netmasks are just the decimal representation of bits used in the network portion of an address.

/12 netmask: 11111111.11110000.00000000.00000000 = 255.240.0.0

/16 netmask: 11111111.11111111.00000000.00000000 = 255.255.0.0 One can calculate the number of usable hosts available in a network using the formula:

2^(32 - X) -2 = Number of Hosts. Where X is the number from the /X CIDR notation. So for a /24 subnet the following will give us usable host addresses…

2^(32 - 24) -2 = 254In a network, we always have 2 addresses pre-allocated. The network address and the broadcast address…

So, for a /24 subnet, the addresses include:

Network address: 192.168.1.0

Usable host addresses: 192.168.1.1 to 192.168.1.254

Broadcast address: 192.168.1.255 The broadcast address is typically the maximum address value of the 4th byte in the range (255), such as 192.168.1.255, hosts use this address when they want to broadcast to anyone listening, hosts of the network listen to this address for broadcasts from other hosts or devices.

The network address is always at 0, it basically is just used to identify the network. Giving the command nmap -sn 10.9.8.0/24 says “Ping scan the last 8 bits of addresses at this network address.”

The binary representation goes up to 255 in each byte, the total number of addresses (including network and broadcast) is 256 becaus a byte can be 255 or 0 which is 256 possibilities.

This website is pretty banger, they do a great job of explaining the network class types in an aesthetically pleasing way. They also have some tools and what seems like a propensity for mischief… https://en.ipshu.com/a-b-c-d-e.

Can we move onto private networks now?

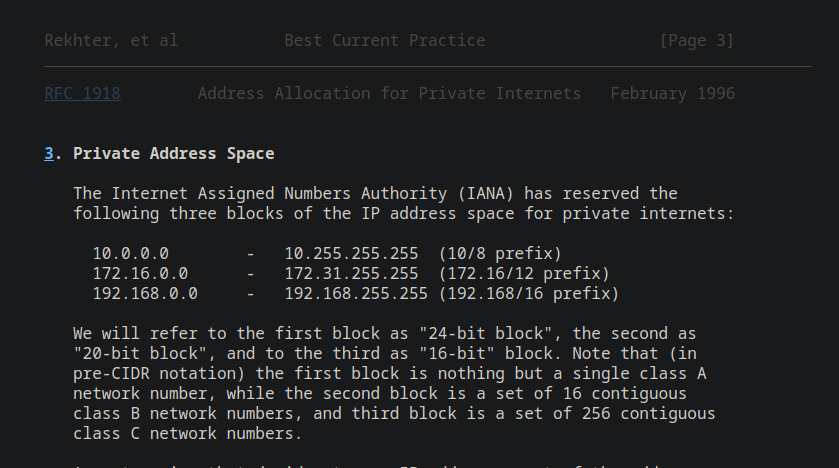

We’re going to reference RFC 1918 https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc1918.

We really just need to understand these ranges. Th 10 network is a class A network. The 172.16 Network is Class B, therefore we know highest static bits must be binary 10 (128). The RFC tells us 12 bits are for network addresses, since we are starting at 172, our first byte is 10101100. That start of the second byte is 00010000 (the 1 is the 12th of 32 bits in the second byte 10101100.00010000) which has a decimal value of 16 (172.16), the maximum value for the second byte is 00011111 or decimal 31, or 172.31 (10101100.00011111). The 192.168 address space has 2 bytes available for hosts.

Don’t overthink private address ranges, just know they exist, they don’t hit the internet, and recognize them when you see them.

APIPA - Automatic Private IP Addressing

If we look at RFC 5735 (https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc5735), we can se the beautiful and unique snowflakes of the networking world. One such entry is the range of 169.254.0.1-169.254.255.255 or the Automatic Private IP Addressing Range.